Wednesday, 28 October 1998

Pictures for posterity

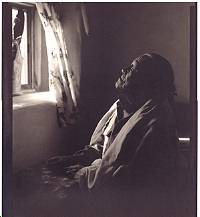

``Terisimo, Morning Light, Taos Pueblo'' (1992) - platinum print by Gary Auerbach

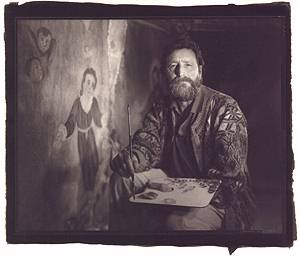

``Carlo'' (1997) - photograph of artist Carlo Giantomassi taken at San Xavier Mission

- platinum print by Auerbach.

Portrait of Marion De Grazia (1997), widow of artist Ted De Grazia - platinum print by

Auerbach.

Photographer adds the platinum touch

It takes time - and moneyA photo that deserves to last 400 years doesn't come easily or cheaply. Last year, Gary Auerbach spent three days traveling around Amsterdam in the rain, searching for a perfect spot to photograph. He found the scene he wanted and, one night, when the weather cleared, he took a single shot of the place, packed up his gear and went home. ``I can't experiment with a lot of negatives,'' Auerbach says. ``This stuff's expensive.'' Most photographers working with a conventional 35 mm camera would shoot a $5 roll of 36-exposure film, get it processed for $3 and printed for $20, and wind up with maybe two dozen nice shots. To get his one nice shot, Auerbach spent $5 for a sheet of film, $7 to process it, and maybe $60 for the platinum and other metals to coat $10 worth of watercolor paper. All this, plus hours of work. It may take Auerbach a day to process his film, two days to make a print and another day to get it matted. Fortunately, much of this work he can do at the kitchen table while keeping an eye on his kids. It's slow, but it doesn't require his full attention hour after hour in a small, dark room reeking of chemicals. Auerbach has tinted some of his photos with pencil or watercolor, but he doesn't make a habit of it. ``People don't appreciate how difficult that is,'' he laments. ``I've ruined more than I've accomplished.'' It's no wonder that he charges $300, plus a sitting fee, for a single portrait. Not exactly a Kmart package deal. But Kmart photographers don't offer platinum prints. WHERE TO SEE THEMGary Auerbach is the resident photographer at Hacienda del Sol Guest Ranch Resort, 5601 N. Hacienda del Sol Road. His works adorn the resort's restaurants, hallways and even restrooms. His platinum prints also have been shown at the Tucson Museum of Art and in venues as distant as Moscow and Geneva. In Tucson, his works may be seen at Hacienda del Sol; Two Coats Trading Company, 7000 E. Tanque Verde Road; and Old Town Artisans, 201 N. Court Ave. |

By James Reel

The Arizona Daily Star

Like a medieval alchemist, Gary Auerbach went searching for an elixir of youth.

He paged through old texts, mixed some chemicals, stirred in a precious metal, and uncovered a way to make you live a thousand years.

In a photograph, that is.

Not impressed? Consider that you're likely to last three times as long as the average photo. You are a far more reliable archival source, a more durable carrier of memories, than your washed-out snapshots.

Conventional black-and-white prints are made with emulsions that contain light-sensitive silver compounds. Over a fairly short time, silver prints decay.

``I realized that no matter how good my photographs might be, I was working in a medium destined to self-destruct,'' Tucson photographer Auerbach writes at his Web site. So he traded his silver emulsions for more stable platinum.

The platinum process Auerbach favors isn't his own invention; it's at least 125 years old.

``It's a simple mixing of simple chemicals using a simple light source, which could be the sun,'' he says. ``It's a low-tech process for super-high quality.''

Auerbach estimates that a maximum of 2,000 photographers in the world do some sort of platinum printing. Of those, Auerbach counts himself as one of no more than 30 photographers specializing in large-format platinum portraits.

Large means 8-by-10 or 11-by-14-inch prints. Because Auerbach specializes in contact prints - transferring the image directly from the negative to the paper, with no enlarger - his cameras have to produce negatives as big as the final picture will be.

Think of the photographers you see in Western or Civil War movies, crouching under a blanket behind a box on a tripod. From the front of the box, an accordion-like extension moves the lens forward and back.

That's precisely what you'd see if you watched Auerbach snap a picture, except he uses natural light rather than an explosive flash.

Platinum photographic materials went off the market after World War II, driving shutterbugs toward silver prints.

In the 1970s, do-it-yourself kits came along that allowed enthusiasts to mix their own platinum-palladium emulsion and coat paper by hand.

``The platinum stains right into the paper, and because platinum is inert, it won't deteriorate,'' Auerbach says. ``The image will last as long as the paper lasts.''

Meaning that 500 to 1,000 years from now, even if Mission San Xavier del Bac has been allowed to melt into the desert, Auerbach's photos of the 1997 San Xavier restoration team will still survive.

Some of his portraits already look a century old, in terms of visual style. There's a close, sharp focus on the subject's face, while the surroundings shimmer in a soft blur.

Scenes of land and city, on the other hand, are remarkably detailed. Even in night shots, Auerbach's large-format platinum landscapes possess a clarity that makes each leaf or brick seem etched onto the paper.

A wrist injury in 1989 ended Auerbach's active chiropractic career, so he turned his attention to photography - only to discover that the commercial photos he'd done in the late '60s were already deteriorating.

Research at the University of Arizona Center for Creative Photography uncovered several techniques for making more permanent photos. Auerbach fell in love with the platinum process.

``It was terrific, no darkrooms were necessary, no more chemical smell,'' he writes. ``Hand coating on the kitchen table and printing outside in the sun, I had the feeling of a pioneer photographer.''

Now, wherever Auerbach travels, he carries his 8-by-10 camera. Lugging the box and bellows and tripod around the world could give him the sort of back pain he used to treat as a chiropractor. But those few pieces of equipment and some negatives are all he needs on the scene. No lights, no batteries, no reflectors.

He can shoot a portrait with no more illumination than sunlight filtered through netting on a window. He photographed artist Carlo Giantomassi during the restoration of San Xavier, hauling his gear up 35 feet of scaffolding and lighting his subject only with the work lamps at hand.

A year ago, Auerbach lugged his 11-by-14 camera up to Mount Hopkins for an early-evening shot of the Multiple Mirror Telescope. But the wind came up, and the camera's bellows, extended an arm's length, was whipped like a boat's sail. A clear shot seemed impossible. But between gusts, Auerbach managed to snap four one-second exposures on the same negative.

At the top of the print is a small white streak, which people assume to be a flaw, a scratch. But it's really Venus moving across the sky through the course of Auerbach's exposures. The photo is now held by the Smithsonian Institution.

But more than grand landscapes or artful nudes, simple portraits of ordinary people may bring Auerbach his greatest longevity as a photographer.

``Portraits can be kept in a family as long as (the photos) last,'' he says. Today, we can pull out moldering photo albums and still look at our ancestors in crisp platinum prints made nearly a century before we were born. But snapshots we took only a couple of decades ago are already washed out.

``With a platinum print,'' Auerbach notes, ``you can tuck it in your drawer, and someone can pull it out 400 years later and it will look the same.''

Gary Auerbach displays his platinum photographs and details his work process at his homepage virtual gallery.